They Call Me Babe

Brenda Dufour

University of Maine

December 13, 2011

“It’s A Good Life if You Don’t Weaken”

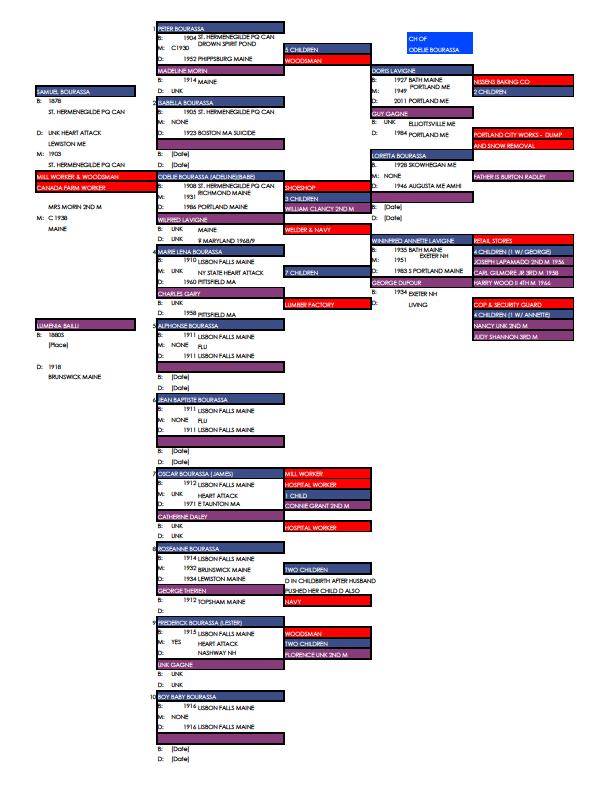

I was born French-Canadian on January 17th, 1908 in St. Hermenegilde, in the Province of Quebec, Canada as the third child of Sinar (Samuel) and Lumenia (Bailli) Bourassa. My father was a farm worker in Canada but he thought he could make more in the United States. He could neither read nor write. In the dead of winter, when I was six weeks old, my family moved to the Lisbon Falls, Maine traveling in a wagon with the few possessions we had. My father was to work in the mill there as a sawmill operator. French-Canadians were welcome at the mills then.

We arrived and moved into a French-Canadian community and lived over a bottle store. My mother stayed at home to care for the family. They made an odd couple as she was six-feet-tall while my father was five-feet-tall. My brother Peter was the oldest born in 1904 followed by my sister Isabella in 1905. Marie was the first born in the United States in 1910 followed by Jean and Alphonse the twins born in 1911,, Oscar in 1912, Roseanna in 1914, Lester in 1915, and an unnamed boy in 1916.

We were poor but I did not know it then. I remember reaching into a hole in the window of the bottle store and grabbing some bottles which I took into the store and sold. Down the street I ran with my pennies and bought a bag of penny candy. As I was walking back home, here came my mom with her big strides. She grabbed me and the bag of candy and off I went into the house with my feet in mid-air. Needless to say, mom shared the candy amongst all of us.

We attended school at the local Catholic school where we all spoke French. No one around us children spoke English. The families brought their place with them from Canada and made the new place similar. We ate creton and tortiere along with other French meals. We sang French songs, read French stories, named the children after French saints, had religious statues, and generally made our home into a copy of the home in Canada. I do not remember Canada so my place is a sub-set to it: Maine. My place was a combination of Maine and Canada as brought to Maine by my parents. Pixley (1996) talks about place stating "That was the place you were homesick for, even when you were there." Maine and my mother’s death taught me self-sufficiency. Anstead (2005) reports that architect Karen Cook states: "My independence and my pride come from Maine. Mainers are proud people. They don't like to be told what to do. And I have a sense of doing things the right and honest way” (p. 1). My friends and family will tell you that I fit this too like Karen.

The twins caught the flu and died at the age of two-months-old. My dad made two small wooden coffins and the boys had pennies put on their eyes to keep them closed. We were Catholic and the local cemetery allowed you to bury babies free along the fence. The cemetery did not keep a record of the burial of these babies. Another infant boy died the same day he was born in 1916. The babies were all born at home and we did not go to doctors.

My mother worked hard at home doing ‘womans’ work washing the clothes with a board, cooking the meals on the kitchen cook stove, watched us kids, and kept the house clean. My mother became pregnant again and she went to a black doctor to get medicine to lose the baby in 1918. She hemorrhaged to death and both she and the baby died. My father took Pete with him to work in the woods and my mother’s mother came to take care of us. That did not last for long. We had several women caretakers but that did not work either. We were taken up on the altar at the end of Mass and offered for adoption. Isabella and I were not adopted so we were taken by train to a Catholic orphanage in Boston. We were separated and punished if we spoke French but we did not know English. We were taught to knit and crochet and sent out to local families as household help. I was ten years old. My real name was Odelie but he priest who took us to the convent misunderstood and I was called Adeline. He also got my birthday wrong and I celebrated it on the 18th for many years. Later I would be known by the name Babe.

Isabella hated moving into homes and doing work so she kept running away. The last time she ran away, she said that if they sent her back she would jump off the Charles River Bridge. One day the nuns came and told me she was dead. She had jumped off the bridge. I ran away and returned to Maine at the age of twelve.

I could not find my family but I stayed in the area. (place) I knew. I then moved to Brunswick and worked as a maid and cook in rich peoples’ homes. I had little education, was female, and French-Canadian so I was lucky to get that. I was lonely and I met a boy in the park. He was wearing a letter jacket. He offered to let me wear it if we had sex. I did not really know much about that but I wanted to wear that jacket so I said yes. His name was Wilfred Lavigne and he was cute. I ended up pregnant and I told him. His father said marry me or join the service. He joined the Navy.

I had a daughter, Doris. I found someone to watch her and I continued to work. I remade clothes given to me as discards from some of the families and kept her dressed. It was hard during the depression. I stood in milk and bread lines and I made do. I became a flapper, going out sometimes dancing in my tight fitting hat and raccoon coat. Eventually I went out with a man named Burton Radley. Those Radleys were a strange family but I was lonely. I got pregnant and was arrested for being pregnant without being married. I was put into a mother’s cottage at the Skowhegan Prison for Women. Doris was put in a foster home on a farm in the country. When Loretta was a year old, she joined Doris and I was put into the regular jail. I got out of prison but the only way I could get my children back was to get married. Wilfred got out of the Navy and we got married in 1931. He claimed Doris but not Loretta but I was able to get both children back. Eventually I had Winifred Annette in 1935. She weighed four pounds and we kept her in a box by the stove to keep her warm. An old Indian woman told me to feed her barley water to help her grow. All my children were born at home with a mid-wife. I had birthed many children as a free midwife for people over the years.

Wilfred and I both worked in the shipyard in Bath during the War. He was a welder and so was I. I had gained weight by then and one day after crawling way into the hold to weld, I got stuck and had to be cut out. That was my last day as a welder! I used to use the twine from the shipyard to crochet clothes for my girls. His parents were also French-Canadian. She stayed at home and he was post master. She used to hide in the bathroom and smoke. Unfortunately she was always burning the wooden sink counter so he would come home and hit her. During prohibition, he made beer in the bathtub and stored it in the cellar. Later he was arrested for stealing money from the mail.

When Annette was ten, Wilfred made a pass at Loretta and I left him after asking my local priest for advice. We moved to Portland and I worked in the local shoe shop. The girls went to public school. Doris graduated and got a job. Loretta started acting out. She would skip school and walk all over Portland. She loved nature and I think if I had lived in the country, she would have been okay. She was a beautiful girl. Once Doris hooked her up on a double date. They rode around in a boat in Deering Oaks Park. Her date put his arm around her and she put her heels through the bottom of the boat and walked home. I made Doris quit work to watch her but that did not work. Eventually the state took her and put her in AMHI.

Doris and I would visit her in Augusta. I tried to get her closer but could not. When she had just turned eighteen, the police came and said she was dying. It was a cold, rainy April day and the window was open. She had a hole in the side of her head but I was told that she had pneumonia. When I asked the doctor to have her moved, he laughed and said I did not have the money for an ambulance. When she died, AMHI did the autopsy as I could not afford to have it done privately.

I married again, a woodsman named Bill Clancy. He ended up a drunk and I divorced him. Eventually, both girls married and left. I continued to work in the shoe shop for many years. As a single woman and mother, I had to earn a living. I did not even finish sixth grade and I was French-Canadian. There was not a lot of employment opportunities for me. In Maine, being French-Canadian is almost a racial thing. Being poor was normal for me and my friends. I had my own community and we helped each other out. Back then, I did not have many choices. I “forged my own identity with the limits of what was possible” as Weiner (2005) states (P. 16).

The wages I made were based on piecework so the faster I stitched the pieces, the more I made. The bosses were all men which is not surprising since men seem to get better jobs and more pay. The shop was huge, very noisy, and hot. I sat next to a window but it did not open. You could not even see through it. I did have a small fan that I brought in myself next to my machine. Later, people would talk about equal pay for both genders but back then, it was the norm for women to earn less and to work in lesser positions.

I saw so many changes in my life. Just think of all the changes. Cars, planes, landing on the moon, telephones, indoor plumbing, television to name a few. I went from scrubbing clothes on a board to a wringer washer and then to an electric one! I had an ice chest for food and a wood cook stove in the kitchen. I was poor but I usually did not think about it. It was normal and I got everything I needed. I worked hard. I survived.

I became naturalized in 1952. I was afraid to do so before that. Lemay (198-9) stated in his report: “They didn't like to become citizens and feared it for more than one reason. They couldn't speak English, and that, let me tell you, was a big handicap. They were afraid of war and might be drafted”. That makes perfect sense to me. I never returned to Canada but I still have an accent. It is not too amazing as I have lived near French speaking people most of my life although I can no longer speak it. I helped raise Annette’s daughter, Brenda, until she was six as Annette had divorced George when Brenda was six-months-old. I would come home from the shoe shop and we would go across the street for an ice cream cone every night. I truly enjoyed that. “It’s a good life if you don’t weaken”.

--------------

Note: Adeline died in 1986. Before she died, she wanted to find her siblings. I was able to locate them but unfortunately, they were all deceased. This story comes from all the interviews I had with Nana. Celeste DeRoche states “oral history can allow historians to more precisely map the change over time between the immigrant and second generation. Oral history brings the issue of change to the fore.”.

References

Anstead, A. (2005). Bangor Daily News. Building on her Past. 11(22). Section C, Pg. 1.

DeRoche, C. I learned things today that I never knew before: Oral history at the kitchen table. Retrieved from http://www.fawi.net/wmst/Deroche.html

Lemay, P. (1938-9). New Hampshire Federal Writers' Project: The French-Canadian Textile Worker. Retrieved from http://memory.loc.gov/wpa/18040142.html

Pixley, J. C. (1996). Homesick for that place: Ruth Moore writes about Maine.

Weiner, M. F. (ed.). (2005). Of place and gender: Women in Maine history. University of Maine Press, Orono: ME