| Bridging the Gap Franco-American Culture in Vermont

By Kim Chase, Burlington, VT

The last French Heritage celebration in Barre brought together

acts from Québec, Vermont and four other New England states.

Those familiar with the traditional music scene will recognize some

big names: Benoit Bourque, Josée Vachon, and Hommage aux Ainés,

just to mention a few. By the Grande Finale, step dancer Benoit Bourque

said to the audience, "We are almost as many up here as you are down

there, so why don't you all come up?" But the musicians refused to

get started without the MC - Martha Pellerin. As usual, it took a

few minutes to locate her. In that particular instance, Martha turned out

to be counting the take for the day to see if she could pay the musicians.

When she finally arrived, she waltzed across the stage with Rhode

Island dance-caller Colette Fournier, then with her own fiddle-playing

son Eric. After that she grabbed the late, great Monsieur Couteau

of Burlington, a man who made an art out of playing knives instead

of spoons. She chose the rest of her victims from the spectators,

many of whom were people she has known all her life. Pretty soon

a good percentage of the audience was dancing in the aisles.

"Do you know Martha?" Sooner or later you're bound to hear that

question if you're interested in anything having to do with Franco-Americans,

or people of French-Canadian descent. Probably sooner than later

because in Franco-American Vermont, all roads lead, eventually, to

Martha Pellerin, a first generation Franco-American from Barre.

La Fête de Saint Jean Baptiste is to people of French descent

what St. Patrick's Day is to Irish Americans. That is, it's a cultural

rather than religious holiday. At the St. Jean Baptiste Day Festival

in Barre this past summer, someone said, "I'm looking for Martha."

"Who isn't?" asked another participant in passing. That's the typical state

of affairs at most Franco-American events in Vermont because even when

she's not the main organizer, Martha is usually in the thick of things

and it's anyone's guess where she can be found. In the case of the

St. Jean Baptiste Day Festival, she happened to be looking for a

piano for the next group of performers, called Folklore Entre Nous

from Plessisville, Québec. The piano was found and the show

went on. Folklore Entre Nous turned out to be almost too talented

for one stage. They sang, step-danced, played piano, violin and

accordion, all with such casual ease that it seemed less a performance

than a party on stage. They had agreed to play for the Festival because,

in the words of Pierre Tardif, "Martha, I could never say no to you."

That seems to be the general consensus among the people Martha has worked

with over the years. Retired assistant librarian and writer Pat Belding

echoes the sentiment: "I've seen the work Martha does and so I'm

happy to help her in any way I can."

And in fact, you would almost have to see one of Martha's productions

to believe she could actually pull it off. Phil Reynolds, executive

director of Catamounts Arts recalls working with Martha on the Franco-Voyageurs

Project which toured New England in 1995. "Martha was performer,

production manager, stage manager and MC, she knew all the other

presenters. She was like the mother of the whole outfit."

Martha is reluctant to take all the credit for the current level

of interest in Franco-American culture and emphasizes the fact that

none of her projects could succeed without community support. "There

are others who contribute in many ways...I am just more visible than

the other activists."

Martha is the Program Developer for ActFANE (Action for Franco-Americans

in the Northeast) and the sole proprietor of Franglais Enterprises,

which seeks to promote an understanding of French-Canadian and Franco-American

culture through traditional arts, lectures, historical exhibits and school

residencies. She is a virtual human data base of Franco-American resources,

which is why her name inevitably surfaces in conversations concerning Franco

Vermonters. She attempts to connect people to each other in order to raise

awareness and broaden support for a culture which has historically been

isolated to the point of invisibility. She prefers the small, kitchen soirées

to bigger venues but worries, "If we continue to work only on a limited,

local level, and don't try to connect all these isolated communities and

find ways that we can share resources, then it's my belief that the

culture will just die away."

Asked why she puts so much energy into her work, Martha responds,

"I am a first generation Franco-American and I myself went through

a period of time when I was not interested in being Franco, I had

let go of my Franco identity. ... But when I was threatened with

the loss of my culture, when my father and several members of my

extended family passed away in a short period of time, I realized

that all of the cultural experience that I'd taken for granted would

soon be gone if I didn't take the opportunity to learn songs, for

instance, and to spend some time understanding what the culture was

all about and what it really meant to me."

Martha grew up immersed in the musical traditions of French Canada.

One of seven children, some born in Québec, she remembers

frequent visits to back St. Sophie, a small town in the in the northern

tip of the Eastern Townships of Québec. Friday night after

work, her mother and father piled the kids into the car and headed

north for a soirée at the Pellerin homestead, built by Martha's

great-grandfather. Family connections across the border have remained

strong and Martha continues to visit her relatives in St. Sophie,

Plessisville and Victoriaville, knowing she will stay, as always, in the

old farmhouse where she first learned some of the songs she sings

today.

"It was not unusual to have sixty people in the house for a New

Year's party," Martha remembers. "Growing up, I was very familiar

with soirées. It was a normal occurrence, lots of singing,

the atmosphere was very warm, very loud. It was something I assumed

every family did. It was not until I was much older that I realized

that not everybody had soirées. To the point that when my

sisters and I were teenagers, we would go to an American party and be

bored to tears. The American parties were so quiet! Compared to what we

experienced as a party at a soirée, these parties in the states

were just as boring as could be and we lost interest in attending

them ."

After the death of her father, Martha began collecting songs

from her relatives. In 1990, she formed the musical group Jeter le

Pont ("Bridging the Gap") along with Dana Whittle and Claude Méthé.

The transition from the intimate soirées to public performances

was not easy. "There was a time when Dana and I were rehearsing in

my mother's kitchen. And she, (my mother) had the bright idea to

invite some of her girlfriends over. So Dana and I were singing these

songs in front of four or five women . We didn't even get past the

first verse and all of them are shaking their heads no. ... And they

would say, 'That's not how it goes.' And one would start singing

it the way she thought it went, she didn't even get past the first

line and somebody else would yell at her, 'No, no, no, you've got it all

wrong!' And they would sing another version . So what we learned was that

there are literally thousands of versions of every one of these songs because

they were taught orally, they're not written down. ...I think it's realistic

to think that these songs were maybe never sung the same twice."

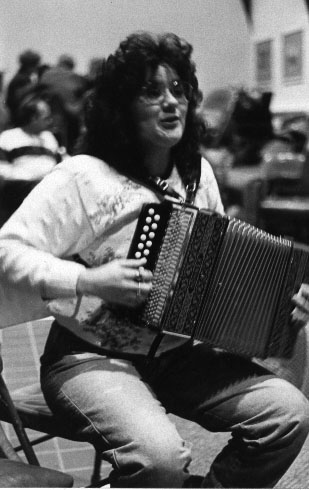

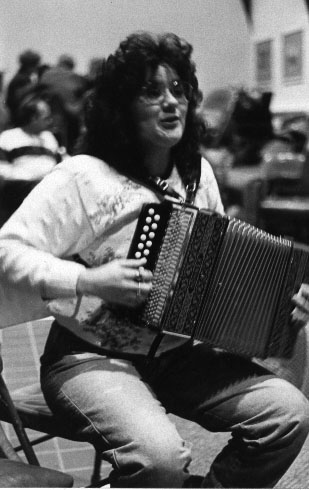

Jeter Le Pont produced two collections of recordings on which

you can hear Martha's strong, vibrant voice accompanied by the vocals

and instrumentals of Dana Whittle and Claude Méthé.

But you would do better to see Martha in person because her gestures,

expressions and rapport with the audience are so typically French-Canadian

and add so much to her performance. Martha has been known to walk

away from a microphone in order to recapture the intimacy of the

soirées she experienced growing up. She sings with a typical

lack of self-consciousness; like many Franco or Québecois musicians

and singers, she doesn't think of her music as a performance. Which gets

to the point of why she doesn't perform much any more.

"Saturday night at the Canadian Club (in Barre), among Francos

who are familiar with the traditional soirées, it's not a

performance to get up and sing. It's simply part of what I would

normally do at a soirée. It feels familiar and comfortable.

When I am at the Barre Opera House or a Festival, among people who

have never experienced a traditional soirée, it's a time to

try to convey some cultural context for the songs I share with the audience

in an entertaining way. The whole purpose of establishing Jeter le Pont

was to create accessibility to Franco-American culture for young

Franco-Americans who don't speak French or speak French but have

no cultural ties to their heritage. It was also to make the Franco-American

culture visible to the general public which knew almost nothing about

us. ... I stopped performing because I felt I was not accomplishing

the original goal. The limited time I have with an audience during

a performance - I felt - only led to creating or contributing to

a stereotype because too little information was shared. I also tried

to recreate the atmosphere of a soirée in a performance venue and

often felt frustrated or unsatisfied."

These days Martha spends most of her time networking with communities

throughout the northeast, creating regional connections. She has been

instrumental, for example, in getting Franco-Americans to submit essays

and memoirs to Le Forum, a publication devoted to the Franco-American

voice. When she is not working on a regional level, she can be found

organizing community projects and bringing performers to Vermont

through events such as the Franco Voyagers Project or the St. Jean

Baptiste Day Festival. "My work primarily involves promoting Franco-American

culture ... the main goal is to present material and events in a

bilingual fashion so that it is accessible to everyone." By "accessible",

Martha means linguistically accessible, and by "everyone" she means

both Francos and non-Francos, and speakers of both French and English.

She is sensitive to the fact that many second and third generation

Franco-Americans, such as her husband and children, do not speak

French and are therefore excluded from traditional cultural activities.

On the other hand, French is often the preferred language of the

immigrant and first-generation population because it is the language

in which they have always carried out their traditions.

"Culture includes language but goes beyond," Martha explains.

"I want to create an environment in which non-French speakers feel

comfortable expressing their identities. This has not been easy because

what makes young Franco-Americans comfortable may eliminate the familiarity

of the traditional cultural setting. It pains me when young people

come to a soirée and don't see anything there that relates

to them as Franco-Americans."

John Drury, Martha's husband, is a third generation Franco-American

whose family maintained few Franco traditions. Consequently, John

has often searched for what it is about him that's French. Last year

on a trip to Acadia in Maine, John and Martha visited an historical

Acadian home. John walked into one of the rooms and gasped, "This

is my grandmother's bedroom!" The layout and furniture were so familiar

he could have been in his own childhood home. "There you are,

John," Martha said. "This is what's French about you."

Knowing how difficult it can be for second and third generation

Franco-Americans to reclaim their heritage, Martha is reluctant to

participate in organizations which do not espouse a policy of inclusion,

total openness to non-French speakers and non-Francos alike. Speaking of

supporters of Franco-American culture who are not Franco-American, she

says, "It's not what's running through your veins. It's your attitude

that counts." Martha's openness extends beyond the world of Franco-Americans,

embracing other ethnic groups, both old and newly immigrated. She

believes that understanding one's own ethnicity can and should lead

to an appreciation of other cultures. "Here in the United States,

we are multicultural and we can all benefit by connecting with other

groups. If we could share our cultural resources we would be a much

richer country."

Anne Sarcka, Community Arts Officer at the Vermont Council on

the Arts, has worked with Martha and values her contribution. "I

have been enormously grateful for the role she has played in helping

young Franco-Americans become more acquainted with their heritage

through discussion and music. ...She has been a vital link in what's

been happening in Vermont and New England with Franco-Americans and

in educating others about Franco-American history."

Martha's dedication to her work is tinged with sadness at the

passing of so many of those who lived the traditions. "I have a melancholy

feeling because I'm losing a lot of the people I've learned songs

from. Every year more than one person dies in a generation of people

who were the tradition bearers. So for me, the responsibility for

passing on the traditions feels stronger and stronger." The difficulty

of the task Martha has set for herself increases as she loses the

older members of her family. Martha recalls thinking, "If I don't

remember the song, no big deal, I'll just call her up. Well, guess

what? She's not there this year."

In her own immediate family, it looks like Martha has succeeded

in transmitting the culture to the next generation. Both of her children

are musicians: Ian, the percussionist, plays spoons, feet and bodrahn

while Eric, the youngest, plays the violin. Since their father, John

Drury, is also an accomplished musician, the boys have always been

surrounded by music and can play and sing a number of Québecois

tunes.

Speaking of the future of Franco-American culture in Vermont,

Martha is cautiously optimistic. She brings her music into schools

as much as possible, working as an artist in residence in order to

build bridges between the remaining elders and younger Francos who

want to learn about their heritage. This critical stage in Franco

history comes at a time when funding is scarcer than ever, so scrambling

for financial support takes up a lot of her time. Despite these challenges,

Martha sees enough happening in the Franco community to be hopeful.

"The culture is going through a natural transition. It's going

to emerge in the next generation looking very different and very

unfamiliar to me, I'm sure. But we have to recognize that it's still

alive. To say that the culture is dead just because it doesn't look

the way we remember it is ridiculous. The way it looked to our parents

is probably not the way it looked to our grandparents and so on.

We just have to accept that."

|